The Façade of Flowing Funds: How Rwanda’s Regime Launders Reputation Through WASH Wash

The Kigali Serena Hotel shimmered, champagne flutes clinked, and a hundred polished stakeholders applauded. Bankers, bureaucrats, and benevolent NGOs unveiled a shiny new financial toy: the Bank of Kigali’s WASH loan. A beacon of progress, they declared, a masterstroke to slake Rwanda’s thirst for clean water and sanitation. But beneath the gloss of this carefully choreographed mise en scène, a more sinister narrative flows – a calculated torrent of misinformation designed not to hydrate the masses, but to irrigate the carefully tended gardens of an authoritarian regime’s international image. As the adage goes, “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink” – especially if the water isn’t actually there, and the horse is shackled by debt and deceit.

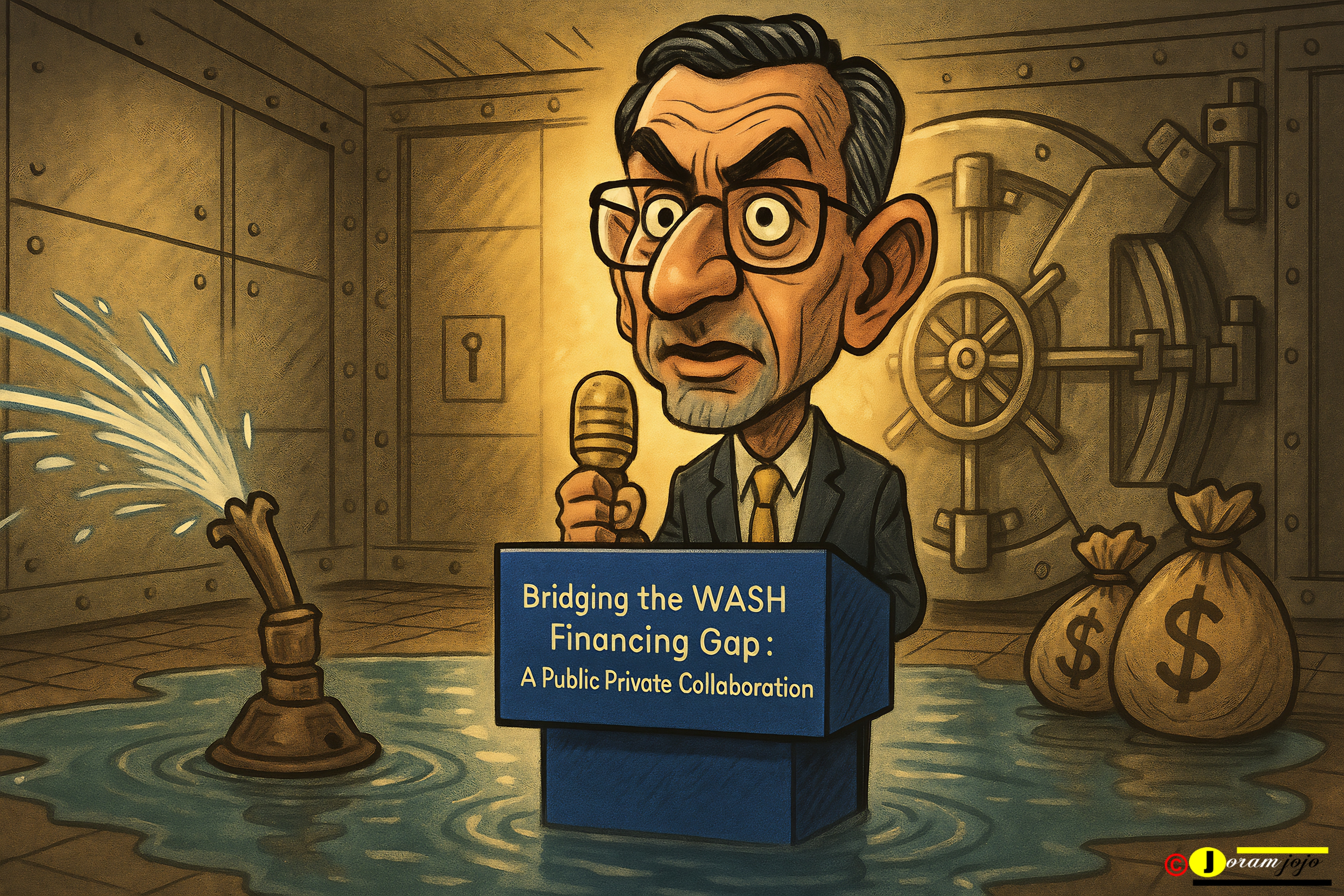

In June 2025, beneath the chandeliers of Kigali’s Serena Hotel, Rwanda’s elite – led by Bank of Kigali’s Darius Mukunzi, UNICEF’s Murtaza Malik, Water For People’s Eugene Dusingizumuremyi, and government officials Gemma Maniraruta and Eng. Dominique Murekezi – unveiled a “transformative” WASH loan product. Promising accelerated universal water access by 2029, this initiative, backed by $54 million in donor legacy, was hailed as innovative blended finance. Yet, a critical examination exposes a Potemkin village of development finance. Beneath the rhetoric of empowerment lies a predatory lending scheme charging 10-14% interest to fragile SMEs in Kayonza and Nyamagabe, demanding 70% collateral, and wilfully ignoring the Rwf 320 billion governance failures sabotaging Rwanda’s water sector. This analysis dismantles the statistical deceit of “90% improved access” masking 12.3% piped water reality, the emotive blackmail weaponising girls’ education to sanctify debt, and the sinister distraction prioritising Serena spectacles over Mageragere Prison’s silenced dissent. We reveal how UNICEF and Water For People inadvertently sanitise authoritarian neglect, why high tariffs will price Nyabugogo’s poorest out of their human right to water, and how this financialised mirage deepens Rwanda’s corrosive crisis of trust. The thirst in Rwanda’s hills demands truth, not debt traps dressed in humanitarian logos.

A Riveting Dissection of the WASH Wash: 20 Points of Critical Exposure

-

The Grand Illusion: Kigali’s Champagne Launch Whilst the Country Thirsts

The scene at the Kigali Serena Hotel was meticulously curated: polished mahogany, starched linen, and the soft clink of crystal as Rwanda’s financial and development elites raised glasses to celebrate the Bank of Kigali’s new WASH loan. Over a hundred “key stakeholders” – government ministers in sharp suits, expatriate development advisors, and banking executives – basked in the air-conditioned opulence. Yet, this carefully staged spectacle, presented as a triumph of partnership and progress, reeked of a grotesque disconnection from the daily realities facing millions of Rwandans. It wasn’t merely a launch; it was a Potemkin village of finance, a shimmering façade erected to mask persistent failure. As the British adage goes, “Fine words butter no parsnips” – and no amount of lofty rhetoric or champagne toasts could obscure the brutal truth: this was a brutal display of priorities, showcasing power and privilege whilst fundamental needs remained unmet.

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this “Grand Illusion” :

-

Theatre Over Substance: The choice of the Serena Hotel – Kigali’s most exclusive venue, synonymous with luxury and foreign dignitaries – was profoundly symbolic. It immediately signalled that this event was designed for and about the powerful, not the water-starved communities in Nyamagabe, Rubavu, or Kayonza. The gathering served no practical purpose for service delivery; its primary function was photo-ops, back-slapping, and generating favourable headlines for the regime and its partners. The “over 100 key stakeholders” were the audience and the performers in a play designed to project an image of dynamic, collaborative progress.

-

The Cruel Juxtaposition: Consider the imagery: delegates sipping mineral water whilst discussing communities relying on distant, contaminated springs. They dined on gourmet cuisine whilst debating sanitation loans for pit latrines. They networked in climate-controlled comfort whilst millions of Rwandans, primarily women and girls, spend hours each day trekking kilometres under the equatorial sun to collect water – water that, even if “improved,” often fails safety standards. The brutality lies in this stark, unspoken contrast. The regime prioritises the appearance of solving the problem for international consumption over the gritty, difficult work of actually ensuring equitable access.

-

Masking Failure with Fanfare: Rwanda’s WASH statistics, selectively touted at such events, conceal harsh truths. Yes, the government boasts of 90% “access to improved water” (2024). But “improved” is a statistical sleight-of-hand. As Eugene Dusingizumuremyi of Water For People admitted at the same event, only 12.3% of Rwandans have piped water at home. A protected spring 2 km away counts as “access,” but it represents a significant burden, often yielding unsafe water. The lavish Serena launch served to distract from this profound failure to deliver convenient, reliable, safe water – the true measure of success. Gathering elites to celebrate a loan product implicitly shifts blame for past shortcomings onto a purported “financing gap,” absolving the state of accountability for implementation inefficiencies or misallocation.

-

The Illusion of Partnership: The event framed this as a glorious tripartite partnership (Bank of Kigali, UNICEF, Water For People). However, this “partnership” occurred in a rarefied bubble, utterly disconnected from the lived experience of ordinary citizens and the small-scale operators it purportedly aims to help. Where were the representatives from struggling rural water associations? The women-led sanitation SMEs from Musanze? Their absence was glaring. This wasn’t grassroots collaboration; it was top-down deal-making among institutional giants, presented as benevolence. The regime leverages the credibility of UNICEF and Water For People to launder its own image, using their presence to imply endorsement not just of the loan, but of its entire approach to WASH and governance.

-

Prioritising Perception over people: The resources poured into this single event – venue hire, catering, security, travel for dignitaries – represent funds that could have directly extended water pipelines or subsidised household connections. The regime’s priority was clear: investing in the spectacle of development to bolster its international reputation as a well-managed, progressive state. This is central to its authoritarian model – meticulous image management. The genuine, urgent needs of its population become secondary to maintaining the carefully constructed narrative of “Rwanda Rising.” The suffering caused by waterborne diseases or the hours lost to water collection are invisible within the Serena’s ballroom; only the triumphant narrative is amplified.

-

A Distraction Tactic: In an environment where political space is tightly controlled and dissent is risky, grand spectacles like this serve a vital function for the regime: they dominate the news cycle. Instead of journalists investigating why only 12.3% have piped water despite decades of effort and billions in aid, or probing allegations of inefficiency within WASAC, they are fed the pre-packaged narrative of “innovation” and “partnership” emanating from the Serena. It drowns out uncomfortable questions and critical voices.

Conclusion: The Bitter Aftertaste

The Serena launch wasn’t merely tone-deaf; it was a deliberate act of political theatre, a Potemkin village constructed not of wood and paint, but of financial jargon, stakeholder lists, and canapés. It showcased a regime adept at performing progress for global audiences, whilst fundamental struggles persist just beyond the hotel’s manicured gardens.

-

The “brutal display of priorities” lies in the cold calculus: the comfort and reputation of the elite matter more than the dignity and health of the millions still hauling water. The champagne may have flowed freely at the Serena, but until the taps flow reliably and safely in every Rwandan home, such events remain nothing more than “fine words” that utterly fail to butter the parsnips – or quench the thirst – of the nation. The grand illusion serves the powerful; the people bear the harsh reality.

-

The Mirage of “Access”: Rwanda’s Statistical Shell Game on Water

The Rwandan government’s triumphant proclamation of “90% access to improved water” and “94% access to improved sanitation” in 2024 isn’t merely a positive statistic; it’s a masterclass in political misdirection, a statistical sleight-of-hand worthy of the most cunning illusionist. This carefully curated figure, plastered across reports and launched from podiums like the Bank of Kigali’s Serena event, creates a Potemkin village of progress, masking a far harsher reality for millions. As the old British adage goes, “You can’t polish a turd” – and no amount of statistical gloss can disguise the fundamental inadequacy of defining “access” in a way that leaves so many Rwandans parched, unsafe, and profoundly dissatisfied.

Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of this deceptive practice:

-

The “Improved” Illusion Defined: The term “improved water source,” as defined by international monitoring (like JMP), includes protected springs, boreholes, and public standpipes. Crucially, it says nothing about:

-

Distance: A “protected spring” counted as “access” could be 5 kilometres away across steep hills in Nyamagabe district. For women and girls primarily responsible for collection, this translates to hours of back-breaking labour daily, lost education, and economic opportunity.

-

Reliability: Does the spring dry up for months? Is the borehole pump frequently broken? “Improved” doesn’t measure functionality or consistent yield. Many communities experience seasonal scarcity or chronic breakdowns, rendering their “access” theoretical.

-

Water Quality & Safety: “Protected” doesn’t equate to “safe.” Springs remain vulnerable to contamination from upstream agriculture, livestock, or inadequate protection. Testing often reveals faecal coliforms or other pollutants, especially after rains. Boiling water requires scarce fuel – a cost and burden omitted from the statistic.

-

Queue Time & Sufficiency: A single public tap serving hundreds in a Kigali informal settlement provides “improved access” but might involve hours of queueing and rationing insufficient water per household.

-

-

The Devastating Reality Check (From Their Own Side!): The sheer cynicism of the regime’s boast is laid bare by data presented at the very same Serena launch event by Eugene Dusingizumuremyi of Water For People Rwanda:

-

Only 12.3% of Rwandans have piped water connections at home. This is the true gold standard of convenient, reliable access – a tap in one’s own compound or dwelling. The gulf between 90% “improved” and 12.3% “piped” is staggering. It reveals the “improved” statistic as largely representing burdensome, communal, and often unsafe collection points.

-

Only 45% of Rwandans are satisfied with their water services. This figure is a damning indictment. If 90% truly had decent access, satisfaction wouldn’t languish below half. It speaks volumes about distance, unreliability, poor quality, high costs (even for “free” sources, time, and effort are costs), and queues that plague the majority counted in the“improved”” bracket.

-

-

Selective Omission as State Policy: The regime’s communication strategy is brutally selective. The triumphant 90% headline is amplified relentlessly. The inconvenient truths revealed by Dusingizumuremyi – the 12.3% piped access and the 45% satisfaction rate – are deliberately omitted from official boasts and press releases. They are buried within reports or mentioned in passing at technical events, never given the prominence of the misleading headline figure. This is not accidental; it’s a calculated strategy to project an image of near-universal success whilst obscuring the persistent, debilitating daily struggle for safe, convenient water.

-

Why This Misdirection Serves the Regime:

-

Meeting Targets on Paper: Rwanda is obsessed with quantifiable development targets. Redefining success down to “improved” sources allows them to tick boxes and claim progress towards SDGs and national goals (like Vision 2050) on paper, without the massive investment required for genuine piped networks.

-

Attracting Investment & Aid: Presenting a narrative of near-universal access (90% sounds impressive to donors and investors unfamiliar with the definitional trickery) makes Rwanda appear a “success story,” attracting further funding and positive international coverage. It launders the regime’s reputation.

-

Deflecting Accountability: By focusing the narrative on the “financing gap” (the Rwf 320 billion cited) needed for further progress, the regime deflects scrutiny from its own performance in managing existing resources, addressing inefficiencies within WASAC, or tackling localised corruption that hinders service delivery. The problem is framed solely as a lack of money, not potential mismanagement.

-

Masking Urban-Rural & Socioeconomic Divides: The “improved” statistic homogenises the experience. It glosses over the stark reality that piped water access (the 12.3%) is overwhelmingly concentrated in urban centres and among the wealthier, whilst rural communities and the poor bear the brunt of distant, unreliable ““improved”sources. The 90% figure hides deep inequality.

-

-

The Human Cost of the Statistical Con: Behind the misleading 90% lie millions of Rwandans:

-

Health: Reliance on distant or unsafe sources perpetuates waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid, particularly impacting children under five.

-

Gender Inequality: The water collection burden falls disproportionately on women and girls, consuming time that could be spent on education, income generation, or rest.

-

Economic Stagnation: Hours lost to water collection and illness hinder productivity and economic activity at household and community levels.

-

Dignity: Queuing for hours for potentially unsafe water is not “access”; it’s a daily indignity.

-

Conclusion: The Bitter Draught Behind the Numbers

Rwanda’s boast of 90% “improved” water access is not a badge of honour; it’s a statistical confidence trick. It exploits a lax international definition to manufacture an illusion of success, whilst the lived reality for most Rwandans – as admitted by their own partners – is one of arduous treks, unsafe water, profound dissatisfaction, and only a tiny fraction enjoying the convenience of a household tap. The regime’s selective omission of the damning 12.3% and 45% figures reveals its priority: managing perception over delivering genuine, equitable service. Truly, “You can’t polish a turd” – and no amount of statistical spin can transform distant, unreliable springs into the safe, convenient, piped water access that constitutes genuine progress.

-

Until the government stops playing definitional games and confronts the harsh reality reflected in its own suppressed data, millions will continue to pay the price for this grand, watery illusion. The parched truth remains: the 90% figure is a mirage, vanishing upon closer inspection, leaving only the dry reality of unmet needs.

-

The 2029 Mirage: Rwanda’s Water Promise Built on Sand

The Rwandan government’s pledge of “universal access to WASH by 2029” echoes through ministerial speeches, development partner reports, and events like the Bank of Kigali’s Serena launch. It’s presented as an immutable national commitment, a beacon of progress. Yet, juxtaposed against the staggering Rwf 320 billion annual funding shortfall cited by these very same officials, this promise crumbles into dust. It’s less a concrete plan and more a cruel mirage shimmering on Rwanda’s development horizon, sustained by wishful thinking and performative gestures. As the British adage warns, “Fine words butter no parsnips” – and no amount of lofty rhetoric can conjure the billions needed to make this dream a reality, especially when the proposed solutions are as inadequate as “using a thimble to empty Lake Kivu.”

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this “Mirage of Universality” :

-

The Chasm Between Rhetoric and Resources:

-

Officials like Gemma Maniraruta (Ministry of Infrastructure) and Murtaza Malik (UNICEF) readily acknowledge the Rwf 320 billion annual gap needed to meet 2030 targets (let alone 2029). This figure isn’t plucked from thin air; it stems from Rwanda’s own Water Sector Financing Strategy. Yet, there is no credible, detailed, publicly accessible roadmap showing precisely how this chasm will be bridged within the next five years. Where will Rwf 1.6 trillion (320bn x 5 years) come from? The silence is deafening. Announcing a target without a viable funding strategy isn’t planning; it’s political theatre.

-

-

The Bank of Kigali Loan: A Drop in the Ocean:

-

The newly launched WASH loan, hailed as a key instrument, exposes the tragic farce. Its maximum loan size per company is Rwf 500 million. Even if every single loan issued was at the maximum (an unrealistic scenario), it would take 640 such loans annually just to cover the stated funding gap. Given the nascent state of private WASH operators and the stringent realities of banking, this volume is pure fantasy.

-

The Lake Kivu analogy is apt. Lake Kivu is one of Africa’s Great Lakes, containing an estimated 550 billion cubic metres of water. Trying to empty it with a thimble isn’t just futile; it’s absurd. Similarly, expecting a Rwf 500m loan product (even multiplied) to address a Rwf 320 billion annual gap is a demonstration of profound disconnect or deliberate obfuscation. It’s a performative gesture, designed to signal action while making negligible material impact on the core problem.

-

-

Ignoring the Scale and Complexity:

-

Achieving genuine universal access isn’t just about money; it’s about monumental logistical, technical, and governance challenges:

-

Geography: Reaching scattered rural communities in Rwanda’s “Land of a Thousand Hills” with piped networks is exponentially more complex and costly than urban projects. The loan product offers no specific solutions for this.

-

Infrastructure: Building and maintaining the vast network of treatment plants, reservoirs, pumping stations, and thousands of kilometres of pipes requires decades of sustained investment and technical expertise far beyond the scope of small loans to SMEs.

-

Sustainability: Ensuring systems function reliably long-term requires robust institutions (like WASAC), effective tariff structures, and local management capacity – areas plagued by known weaknesses, not addressed by this loan.

-

-

The loan focuses narrowly on private operators and SMEs, ignoring the massive public infrastructure backbone required for true universality. It tackles fragments, not the system.

-

-

A Convenient Diversion:

-

The constant repetition of the “2029 Universal Access” goal serves a vital function for the regime: it shifts the timeline and deflects scrutiny. It frames the current lack of piped water (only 12.3%) not as a present failure, but as a future challenge requiring more resources. “Just wait until 2029” becomes the mantra, absolving officials of accountability for today’s shortcomings in service delivery, maintenance, or equitable distribution. It kicks the can down a very short, rapidly disappearing road.

-

-

Eroding Credibility and Trust:

-

Announcing grand, unattainable targets without a plausible plan ultimately damages credibility. When 2029 arrives and universality remains a distant dream (as it inevitably will, given the current trajectory), public disillusionment will grow. Communities in Kayonza or Nyaruguru who heard the promise but still trek to springs will rightly feel betrayed. The gap between promise and lived reality fuels cynicism and erodes trust in institutions. It’s a recipe for long-term disillusionment.

-

-

The Role of Partners in Perpetuating the Mirage:

-

Development partners like UNICEF and Water For People, while acknowledging the funding gap, lend legitimacy to the 2029 target by participating in events promoting patently inadequate solutions like this loan. Their presence implicitly endorses the feasibility of the timeline, even if their technical staff know otherwise. This collaboration risks becoming complicit in maintaining the illusion.

-

Conclusion: The Thimble and the Lake

Rwanda’s promise of universal WASH access by 2029, repeated like a mantra by officials amidst the Serena Hotel’s opulence, is exposed as a grand and tragic illusion when held against the brutal arithmetic of the Rwf 320 billion annual funding gap. The Bank of Kigali’s loan scheme, however well-intentioned in parts, is utterly insignificant against this vast financial chasm. It is indeed akin to using a thimble to empty Lake Kivu – a gesture so futile it borders on farce.

-

This mirage serves the regime’s immediate need for positive headlines and international plaudits, but it does a profound disservice to the Rwandan people. It postpones accountability, distracts from systemic failures in governance and planning, and ultimately sets the population up for disappointment. Fine words butter, no parsnips. Lofty promises of universal access by 2029, unsupported by credible funding strategies and reliant on financial instruments as inadequate as this loan, will not bring a single drop of safe, piped water to the homes of the millions still waiting. Until the government confronts the true scale of the challenge with honesty, transparency, and a viable, fully costed national plan backed by real resources, the 2029 target will remain nothing more than a shimmering, cruel mirage on Rwanda’s development landscape. The parched reality endures.

-

The Serpent’s Bite: How High-Interest Rates Poison Rwanda’s Water Promise

Beneath the benevolent veneer of the Bank of Kigali’s WASH loan product lurks a venomous reality: interest rates of 10-14%. Framed as “tailored finance” and “support” for a nascent sector providing essential public goods, these rates are nothing short of predatory lending camouflaged as philanthropy. In a developing nation like Rwanda, where profit margins for small-scale water operators are razor-thin and the service itself is a fundamental human right, saddling entrepreneurs with such debt is like “selling a drowning man a glass of water” – it exploits desperation while pretending to offer salvation. This isn’t empowerment; it’s a financial trap ensuring many SMEs will drown under the weight of debt servicing, turning a promise of progress into a chilling prospect of dispossession.

Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of why these rates are so pernicious in the Rwandan context:

-

The Essential Nature of the Goods vs. Commercial Realities:

-

Water and sanitation are not luxury commodities; they are fundamental human rights and public health necessities. Treating their provision purely through a high-interest commercial lending lens is fundamentally flawed. The societal benefit of universal WASH access vastly outweighs narrow bank profitability targets.

-

Nascent Sector Vulnerabilities: As Darius Mukunzi (BK) admitted, the WASH sector in Rwanda is “emerging.” Private operators, especially in rural areas, face immense challenges: low population density, high infrastructure costs, difficulty collecting tariffs from impoverished communities, seasonal fluctuations, and limited technical capacity. Their businesses are inherently fragile and low-margin. High-interest debt massively amplifies these risks.

-

-

The Crushing Math of Debt Servicing:

-

Example: A small water utility in Rubavu district borrows Rwf 200 million at 12% over 5 years. Over the loan term, they will pay approximately Rwf 67 million in interest alone (excluding fees). That’s Rwf 11.2 million per year just to service the debt.

-

Impact: This forces operators into an impossible bind:

-

Raise Tariffs: To cover debt costs, they must charge users more. But this prices water out of reach for the poorest, undermining the goal of universal access and violating the principle of affordability. It turns a human right into an unaffordable commodity.

-

Cut Costs: Skimping on maintenance, water quality testing, or staff training. This leads to system breakdowns, unsafe water, and ultimately, service failure – the exact opposite of sustainability.

-

Risk Collapse: If revenue falls short (due to drought, non-payment, or competition), the operator defaults. The bank seizes collateral (often essential equipment or property), destroying the business and leaving the community without service. This is the “drowning in debt servicing” outcome.

-

-

-

Predatory Dynamics Camouflaged as “Support”:

-

Exploiting Need: The regime and BK are acutely aware of the desperate need for WASH investment and the lack of alternatives for operators. Offering loans under these terms exploits that vulnerability.

-

Philanthropic Veneer: The partnership with UNICEF and Water For People, the rhetoric of “sustainable development,” and “supporting underserved areas” provide a smokescreen of altruism, masking what is fundamentally a high-risk, high-reward commercial venture for the bank. The “special incentives” (slightly lower collateral, Rwf 15m collateral-free for women) are token concessions that don’t negate the core burden of the interest rate. It’s like offering a bandage for a gunshot wound while charging exorbitantly for it.

-

“Tailored Finance” Myth: True tailored finance for a fragile, essential public service sector would involve deeply concessional rates (near 0% or inflation-linked), much longer grace periods, and repayment structures directly linked to revenue generation or project milestones. 10-14% is standard SME banking territory, utterly untailored to the unique challenges and public importance of WASH.

-

-

The Broader Economic Poison:

-

Crowding Out Public Investment: Framing this loan as a key solution subtly suggests the private sector (via expensive debt) should bear the brunt of financing essential public goods, letting the state off the hook for necessary major public investment in bulk infrastructure.

-

Perpetuating Inequality: High tariffs resulting from debt servicing disproportionately impact the poorest, exacerbating existing inequalities. The “universal access” goal becomes meaningless if the service is unaffordable.

-

Discouraging Genuine Entrepreneurs: Savvy potential investors will see the debt trap inherent in these terms and avoid the sector, leaving it to the desperate or the naïve. This stifles genuine sustainable private sector development.

-

Eroding Trust in Finance: When SMEs inevitably fail under this debt burden, it breeds cynicism about financial institutions and “development” initiatives, making it harder to mobilise capital for genuinely beneficial projects in the future.

-

-

The Chilling Prospect: Debt as a Control Mechanism:

-

The spectre of default and asset seizure gives the bank (and potentially the state, given BK’s quasi-state status) significant leverage over WASH operators. This could subtly influence operational decisions, service areas, or even political alignment, turning a financial instrument into a tool of control over a vital public service sector.

-

Conclusion: Extracting Profit from Thirst

The Bank of Kigali’s 10-14% WASH loan interest rates are the serpent coiled in the oasis. They transform a programme ostensibly designed to deliver life-sustaining water and sanitation into a mechanism for extracting profit from the very communities it claims to serve. It is the starkest example of “selling a drowning man a glass of water” – exploiting dire need for commercial gain under a facade of benevolence.

True empowerment for Rwanda’s WASH sector would involve patient, low-cost capital aligned with the long-term, public-good nature of the service – perhaps via dedicated state development banks with concessional terms, significant grant funding blended intelligently with soft loans, or genuine results-based financing from donors. High-interest commercial debt is fundamentally misaligned with the goal of universal, affordable, sustainable access. It ensures that the only liquidity flowing freely will be the tears of failed operators and the profits of the bank, while the promise of clean water for all remains a cruel mirage, poisoned at its source by the venom of usury disguised as aid. The Rwandan people deserve better than to have their basic rights mortgaged at extortionate rates.

-

-

The Collateral Mirage: Rwanda’s WASH Loan Trap for the Asset-Poor

The Bank of Kigali’s WASH loan product presents its collateral concessions – 70% security requirement (down from 80-100%) and Rwf 15 million collateral-free loans for women in hygiene – as bold, progressive steps. In the rarefied air of the Serena launch, it sounded like enlightened finance. On the rutted tracks of Kayonza or the crowded slopes of Nyabugogo, however, this “concession” reveals itself as little more than elaborate smoke and mirrors. It’s tokenism masquerading as transformation, offering crumbs whilst ignoring the banquet of barriers facing most operators. As the British adage starkly puts it: “You can’t get blood from a stone.” And for countless Rwandan WASH entrepreneurs, demanding 70% collateral for essential equipment like sludge trucks is precisely that – a brutal demand for blood where only stone exists.

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this “Collateral Conundrum” in the Rwandan reality:

-

The Brutal Mathematics of 70%:

-

Sanitation Truck Example: A basic, new vacuum truck capable of servicing pit latrines in peri-urban areas costs roughly Rwf 50-70 million. A 70% collateral requirement means an operator needs Rwf 35-49 million in unencumbered, bank-acceptable assets (land, property, heavy machinery) just to secure the loan. For a small sanitation SME in Musanze or Rusizi, this is an insurmountable hurdle. Where does a start-up or a community-based operator find Rwf 35 million in collateral? They simply don’t possess it. The “reduction” is meaningless against the sheer scale of the asset value required.

-

-

The Used Truck Trap & the 10% Mirage:

-

BK offers financing for used trucks “up to 7 years old” with a 10% down payment. This sounds helpful until you examine the risks:

-

Valuation & Reliability: Valuing a 7-year-old sludge truck is fraught. Banks will undervalue, demanding higher collateral relative to loan size. Older trucks break down constantly in Rwanda’s tough conditions. Repairs are expensive and downtime means no revenue, jeopardising repayments.

-

The Down Payment: 10% of Rwf 40m (a cheap used truck) is still Rwf 4 million – a massive upfront cash requirement for a small operator, likely requiring another loan or selling vital assets.

-

The Debt Spiral: Combining a high-interest loan (10-14%) on a depreciating, unreliable asset with high operating costs creates a perfect storm for default. When the truck breaks, revenue stops, but the bank repayments don’t.

-

-

-

Rwf 15m “Collateral-Free” for Women: Tokenism Exposed:

-

While commendable in principle, Rwf 15 million is utterly inadequate for the capital needs of meaningful WASH businesses beyond the smallest hygiene kiosks.

-

Hygiene Scale: Setting up a significant soap production unit, a sanitary pad manufacturing line, or a proper waste collection service requires far more capital. Rwf 15m buys stock, not transformative capacity. It keeps women in micro-stalls, not leading sector change.

-

Ignoring Core Needs: For women wanting to enter sanitation (e.g., operating emptying services) or water supply, this collateral-free ceiling is irrelevant. They immediately hit the brick wall of the 70% requirement for essential equipment or infrastructure. It’s a separate, constrained box, not a pathway to significant sector participation.

-

-

-

The “Emerging Sector” Contradiction:

-

Darius Mukunzi (BK) justifies special terms because WASH is “emerging.” Yet, demanding 70% collateral is standard banking practice for established sectors. If the sector is truly nascent and high-risk (which it is), why isn’t the collateral requirement radically lower (e.g., 30-40%) backed by robust technical assistance and blended finance guarantees? The 70% figure shows BK’s risk aversion overrides its purported developmental mission. It’s business as usual, lightly disguised.

-

-

The Asset-Poor Reality of Rural Operators:

-

Consider a water committee in Nyamagabe managing a small spring system. Their “assets” are community goodwill, rudimentary pipes, and perhaps a small storage tank – none of which are likely bank collateral. They need Rwf 30m to upgrade pipes and meters. BK’s 70% rule demands Rwf 21m in acceptable assets they simply don’t have. The stone has no blood to give. The “reduced” collateral requirement is a hollow gesture, locking out precisely the rural operators the scheme claims to target.

-

-

WASAC’s “Framework”: Vague Promises vs. Banking Reality:

-

Eng. Dominique Murekezi (WASAC) mentioned a “framework to support small private investors.” But where are the details? Does it provide credible loan guarantees to reduce the collateral burden for banks? Does it offer asset leasing? Without concrete, accessible mechanisms translating this vague “framework” into tangible collateral relief at the bank counter, it remains bureaucratic vapourware, offering no real solution to the operator struggling before the BK loans officer.

-

-

The Brutal Outcome: Exclusion & Stagnation:

-

The collateral requirements, even “reduced,” ensure that only businesses already possessing significant assets (urban entrepreneurs, established companies diversifying) can access meaningful loan amounts. Truly grassroots, community-based, or innovative start-ups without existing wealth are systematically excluded. This stifles innovation and entrenches existing inequalities, doing nothing to “unlock private sector participation” in underserved areas. It protects the bank, not the sector.

-

Conclusion: Smoke, Mirrors, and the Stone-Cold Reality

Bank of Kigali’s collateral “concessions” are a masterclass in financial illusion. Reducing requirements to 70% is like offering a discount on a Rolls-Royce to someone who can barely afford a bicycle – the fundamental barrier remains utterly intact. The Rwf 15m women’s loan is a well-intentioned but patronising token, insufficient for transformative ventures and irrelevant for sanitation or water infrastructure. Both fail the core test: enabling new, asset-poor entrants to access the capital needed for significant WASH service delivery.

-

The brutal truth, as the adage “You can’t get blood from a stone” so aptly captures, is that most Rwandan WASH operators – the very ones meant to drive universal access – possess neither the established assets nor the upfront capital to meet BK’s terms. The smoke of “reduced collateral” and the mirrors of “collateral-free for women” distract from this stone-cold reality: the loan product is structurally designed to favour the relatively wealthy and established, not to catalyse a revolution from below. It protects the bank’s balance sheet while offering false hope to the parched. Until genuine, radical collateral innovation emerges – deep guarantees, asset financing, truly patient capital – the promise of private sector-led WASH expansion for the poorest communities will remain just another cruel mirage on Rwanda’s development landscape, obscured by the cynical smoke and mirrors of Kigali’s banking elite. The stone remains bloodless, the thirst unquenched.

-

The Emperor’s New Finance: Rwanda’s Donor-Fuelled “Innovation” Farce

When UNICEF’s Murtaza Malik stood before the glittering chandeliers of the Kigali Serena and hailed the Bank of Kigali’s WASH loan as “innovative financing,” it wasn’t merely optimistic – it was a masterstroke of semantic sleight-of-hand. The core model, reliant on donor-backed “risk-sharing mechanisms” and promises of future “green sector funds,” represents not a breakthrough in commercial finance, but the tired old wine of aid dependency poured into a shiny new bottle labelled “Bank.” It’s a satirical spectacle worthy of Swift: dressing perpetual reliance on foreign largesse in the bespoke suit of financial innovation. As the old British adage bitingly observes, “You cannot make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear” – and no amount of rebranding can transform donor dependence into genuine commercial market dynamism.

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this donor-dependency masquerade:

-

The “Innovation” Mirage Exposed:

-

“Risk-Sharing Mechanisms”: This sanitised term usually means donor guarantees (from UNICEF, Water For People, or other development agencies). If a borrower defaults, the donor, not BK, absorbs a significant portion (often 50-80%) of the loss. This isn’t innovation; it’s classic development aid de-risking, used for decades. The bank takes less risk, but the financial system hasn’t truly internalised or priced the WASH sector’s realities. The risk is simply transferred to aid budgets.

-

Future “Green Sector Funds”: Mentioning funds that might open in 2026 (as Darius Mukunzi did) is pure vapourware. It’s a promissory note, not present capital. Relying on uncertain future donor grants to make a current loan product viable exposes its fundamental fragility. True market innovation wouldn’t hinge on hypothetical future subsidies.

-

-

Why It’s Not “Unlocking Commercial Finance”:

-

Risk Perception Unchanged: Commercial banks lend based on perceived risk and return. The donor guarantees temporarily shield BK, but they do nothing to change the inherent risk profile of lending to fragile WASH SMEs in the eyes of other commercial banks. BK participates because it’s de-risked by aid, not because it suddenly sees WASH as a prime commercial opportunity.

-

No Market Transformation: Genuine “unlocking” would mean commercial banks, without donor crutches, developing the appetite, expertise, and products to sustainably finance WASH based on its merits. This model does the opposite: it perpetuates the notion that WASH is only bankable with heavy donor subsidy. It entrenches dependency.

-

Bank Profit, Donor Risk: BK still charges 10-14% interest – a healthy commercial return – while the donors shoulder the bulk of the default risk. It’s a sweetheart deal for the bank: profits are privatised, risks are socialised (onto aid budgets). This isn’t catalysing a market; it’s exploiting a subsidy.

-

-

Rebranding Aid Dependency:

-

The Logo Swap: The only tangible “innovation” is slapping the Bank of Kigali logo onto what is, at its core, a donor-subsidised credit line. Instead of the Ministry of Infrastructure or an NGO directly administering a grant or soft loan, the money is funnelled through a commercial bank, allowing the regime and its partners to claim “private sector engagement” and “commercial sustainability.” The substance, however, remains profoundly dependent on external aid money.

-

Satirical Duplicity: The sheer audacity of framing this as a shift away from traditional aid is darkly comical. It’s like claiming you’ve “innovated” your household budget because you started paying the grocer with your uncle’s monthly allowance instead of collecting the food parcel yourself. The source remains unchanged.

-

-

Why the Regime & Partners Push This Narrative:

-

Regime Credibility: For Kigali, it feeds the “Rwanda Rising” mythos – showcasing “sophisticated” financial instruments and private sector leadership, distancing itself from the image of a perpetual aid recipient. It’s reputation laundering.

-

Donor Justification: For UNICEF and Water For People, it offers a narrative of “catalysing markets” and “leveraging private capital,” which is currently fashionable in donor circles. It helps justify their continued funding and presents them as cutting-edge, even while recycling old aid models. Ticking the “Innovation” box trumps admitting persistent dependency.

-

Bank PR: For BK, it’s pure prestige – positioning itself as a “development bank” leader while enjoying de-risked profits. Good PR for attracting other donor-backed deals.

-

-

The Rwandan Reality Check: Perpetuating the Cycle:

-

No Path to Self-Sufficiency: This model does nothing to build a self-sustaining Rwandan WASH financing ecosystem. When the donor guarantees expire or the “green funds” fail to materialise, the “innovative” product will likely vanish, leaving the sector no more commercially attractive to banks than before.

-

Distracting from Systemic Issues: The focus on this financial sleight-of-hand distracts from tackling the real barriers to commercial finance: weak operator capacity, unclear regulatory frameworks, affordability constraints, and governance issues within WASAC. Dressing aid up as a bank loan doesn’t fix these.

-

The Kayonza Test: Imagine a small pit-emptying enterprise in Kayonza. They get a BK loan thanks to a UNICEF guarantee. If they struggle (highly likely given interest rates and operational challenges), UNICEF eats the loss. BK is unharmed. The operator is ruined. The community loses service. The fundamental unviability remains. Where’s the innovation? Only in the accounting.

-

Conclusion: The Sow’s Ear Stays

Murtaza Malik’s “innovative financing” is exposed as a satirical charade, a Potemkin village built on donor dollars. The Bank of Kigali’s WASH loan, propped up by risk-sharing and future fund fantasies, is the emperor’s new clothes of development finance. It represents not a liberation from aid dependency, but its cunning rebranding – aid with a bank logo and a hefty interest rate attached.

-

Truly, “You cannot make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.” No amount of financial jargon, Serena Hotel launches, or partnerships with blue-chip NGOs can spin the stubborn reality: Rwanda’s WASH sector remains fundamentally reliant on the generosity of foreign donors to attract even the most risk-averse commercial lending. This isn’t innovation; it’s institutionalised dependency with a fresh coat of paint and a higher price tag for the borrower. Until genuine commercial viability is built through addressing the sector’s root causes – not just papering over them with donor guarantees – Rwanda’s “innovative” WASH finance will remain a satirical tale of repackaged aid, where the only silk is found in the ties of the bankers and bureaucrats counting the donor-subsidised profits, while the sow’s ear of dependency remains firmly in place for the communities they purport to serve. The farce continues, financed not by the market, but by the very aid it claims to transcend.

-

The Silent Gorilla: How Governance Failures Are Drowning Rwanda’s Water Hopes

Amidst the polished rhetoric of the Bank of Kigali’s Serena Hotel launch – the earnest talk of “financing gaps,” “innovative products,” and “partnerships” – lurked an immense, unacknowledged presence: the gorilla of governance failure and corruption within Rwanda’s WASH sector. While officials and partners meticulously parroted the Rwf 320 billion funding shortfall as the sole barrier to universal access, they performed a collective act of sinister omission, carefully avoiding any critical analysis of mismanagement, inefficiency, or outright corruption plaguing existing systems. Water For People’s nebulous pledge to “improve governance” was classic NGO-speak – a meaningless incantation designed to placate, not probe, assiduously avoiding any implication of state culpability. As the British adage starkly warns: “None so blind as those who will not see.” And in Kigali’s halls of power, the blindness towards this gorilla is wilful, self-serving, and devastating for Rwanda’s parched populace.

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this glaring omission:

-

The “Financing Gap” Smokescreen:

-

Focusing exclusively on the lack of money is a convenient diversion. It frames the problem as purely technical and resource-based, absolving those managing the existing resources of responsibility. It suggests that if only Rwf 320bn magically appeared, universal access would follow – a naive fantasy ignoring the gorilla-sized question of implementation capacity and integrity.

-

This narrative serves the regime perfectly: it portrays them as ambitious visionaries hamstrung only by insufficient funds, not by their own institutions’ failings.

-

-

Mismanagement & Inefficiency: The Leaking Pipes of the System:

-

WASAC’s Woes: Rwanda’s Water and Sanitation Corporation (WASAC) has long-faced criticism (often whispered, rarely published) over operational inefficiencies. Think chronic water losses from ageing, poorly maintained urban networks (non-revenue water rates potentially exceeding 40% in some areas – far above efficient utility benchmarks). Think delayed repairs, billing irregularities, and uneven service quality even in connected areas. Pouring money into a system with such leaks is like filling a bucket with holes.

-

District-Level Dysfunction: Decentralisation placed significant WASH responsibility on districts. Many lack the technical expertise, financial management skills, or oversight capacity to effectively plan, implement, and maintain complex water schemes. Funds are often misallocated, projects delayed, and maintenance neglected, leading to premature system failure – a stark reality in rural areas like Nyamagabe or Kayonza, where broken boreholes litter the landscape. Where is the analysis of why these systems fail so soon?

-

Poor Asset Management: A critical lack of robust asset registers and maintenance planning means the true condition and value of existing WASH infrastructure (pipes, pumps, treatment plants) is often unknown, hindering efficient investment and prioritisation.

-

-

The Unspoken Gorilla: Corruption & Patronage:

-

Procurement Ploys: The WASH sector, with its large infrastructure contracts, is notoriously vulnerable to corruption. Inflated tenders, bid-rigging, kickbacks, and the awarding of contracts based on patronage rather than merit siphon off precious resources before a single pipe is laid. The lack of truly independent oversight bodies and a controlled media environment makes exposure and accountability rare. This gorilla doesn’t just sit in the room; it feasts on the budget.

-

Fund Diversion & Misuse: Reports from auditing bodies (when they dare surface) and anecdotal evidence frequently point to the diversion of WASH funds for other purposes or straightforward embezzlement at local levels. Resources meant for village water points end up lining pockets or funding local officials’ pet projects.

-

“Connection Fees” & Informal Payments: Even at the point of service, informal payments or inflated “connection fees” can create barriers for the poor, enriching intermediaries or low-level officials. This undermines affordability and equity.

-

-

Water For People’s Vague Incantation: “Improving Governance”:

-

Their stated goal is utterly hollow without specificity and teeth. What governance aspects? How will they be improved? Who will be held accountable? It’s a classic NGO fig leaf – acknowledging governance is somehow a factor while meticulously avoiding any critique that might implicate their government partners or jeopardise their operating permit.

-

It allows them to maintain access and relationships while performing a ritualistic nod towards a complex problem they have no power (or perhaps will) to seriously address. It’s complicity through vagueness.

-

-

Why the Silence is Sinister:

-

Protecting the Regime: Criticising governance failures, let alone corruption, within Rwanda’s tightly controlled system is perilous. The regime prioritises an image of technocratic efficiency and zero tolerance for corruption (selectively enforced). Admitting systemic flaws in a vital sector like WASH shatters this carefully constructed myth. Hence, the omission is enforced.

-

Donor Complicity: Major donors (like those funding UNICEF and Water For People) often prioritise maintaining access and “partnership” over rocking the boat with uncomfortable truths about governance. They fear being ejected. This creates a conspiracy of silence, where the gorilla is politely ignored lest it charge.

-

Eroding Trust & Effectiveness: This silence is profoundly corrosive. It ensures the real problems – the leaks, the graft, the ineptitude – persist and fester. It guarantees that even if more funds were found, a significant portion would be wasted or stolen, perpetuating the cycle of failure and disillusionment among ordinary Rwandans. They see the gorilla, even if the elites in Kigali pretend not to.

-

Conclusion: Blind Eyes, Broken Pumps

The Serena launch’s deafening silence on governance and corruption wasn’t an oversight; it was a strategic, sinister omission. By fixating solely on the “financing gap,” the regime and its partners perform a pantomime of problem-solving, wilfully blind to the gorilla of mismanagement and malfeasance that systematically sabotages Rwanda’s water and sanitation systems. Water For People’s vague murmurs about “governance” are a cowardly whisper in the face of this roaring reality.

-

“None so blind as those who will not see.” The blindness in Kigali is a choice. It’s a choice to protect power structures, preserve international image, and maintain donor flows, rather than confront the rot undermining the very goal of universal access. Until this gorilla is acknowledged, named, and tackled with genuine transparency, accountability, and independent oversight – not NGO platitudes – no amount of “innovative finance,” whether from BK or donors, will deliver more than a trickle of progress. The Rwf 320 billion gap is daunting, but the gaping hole in governance integrity is what truly drowns hope. The broken pumps in Nyamagabe and the dry taps in Kayonza stand as silent, brutal testaments to the gorilla in the room that power refuses to see, while the people pay the price in sweat, sickness, and stolen futures.

-

The Private Sector Mirage: How Rwanda’s Loan Trap Sets Up Water Entrepreneurs to Fail

The Rwandan regime’s fervent championing of private sector involvement as the panacea for its WASH crisis reached a crescendo at the Bank of Kigali’s Serena launch. Yet, in a moment of unintended candour, Eng. Dominique Murekezi of WASAC Development Ltd laid bare the brutal reality: private operators grapple with “weak business planning” and “short-term contracts.” The regime’s solution? Tossing them a high-interest loan and whispering platitudes about “unlocking potential.” This isn’t empowerment; it’s like commanding a drowning man to build a castle in the air – a cruel fantasy, ignoring the raging currents pulling him under. The loan doesn’t fix the systemic rot; it merely finances the operator’s journey towards inevitable failure.

Here’s a comprehensive breakdown of this “Private Sector Mirage” :

-

The Regime’s Rhetoric vs. Murekezi’s Reality:

-

The Official Narrative: The state posits dynamic, efficient private operators as the engine to drive universal access, filling the void left by strained public utilities. The BK loan is framed as the fuel for this engine.

-

The Unvarnished Truth (from the State’s Own Partner): Murekezi’s admission exposes the sector’s raw fragility. Operators aren’t dynamic entrepreneurs; they’re often under-resourced, inexperienced individuals or community groups struggling with:

-

“Weak Business Planning”: Many lack basic skills in financial management, market analysis, tariff setting, maintenance budgeting, or long-term strategy. They operate hand-to-mouth.

-

“Short-Term Contracts”: Operators frequently work on precarious, limited-term agreements (e.g., 1-3 years) with district authorities or WASAC. This provides zero security of tenure, discouraging long-term investment and leaving them vulnerable to non-renewal based on political whims or underperformance against unrealistic targets.

-

Unviable Operating Environments: Thin profit margins (due to low tariffs, collection issues, high operational costs), complex logistics (especially rural), lack of technical backup, and unpredictable demand create a fundamentally hostile environment for sustainable business.

-

-

-

Why the High-Interest Loan is a Poisoned Chalice:

-

Addressing Symptoms, Not Causes: The loan throws money at the symptom (lack of capital) while utterly ignoring the diseases identified by Murekezi: poor planning skills and unstable contracts. It’s like giving a powerful engine to a driver who hasn’t passed their test and whose car has no wheels.

-

Amplifying Risk, Not Mitigating It: Saddling an operator with weak business acumen and a shaky contract with 10-14% debt is reckless. It adds the crushing burden of fixed monthly repayments to an already precarious cash flow. One dry season, one major breakdown, one delayed contract renewal, or poor tariff collection can trigger instant default.

-

The Kayonza Pit-Emptier’s Nightmare: Imagine a small sanitation SME in Kayonza. They secured a Rwf 80m loan at 12% to buy a truck. Annual interest: ~Rwf 9.6m. Their 2-year contract isn’t renewed. Suddenly, they have an asset they can’t fully utilise and a massive debt. The bank seizes the truck. The operator is ruined. The community loses service. The loan accelerated their collapse.

-

-

Systemic Issues Demanding Systemic Solutions (Ignored by the Loan):

-

Building Real Capacity: True support would involve intensive, long-term business development services: training in financial literacy, operational management, maintenance planning, customer relations, and technical skills. This requires patient investment, not just debt.

-

Stabilising the Operating Environment:

-

Longer, Secure Contracts: Operators need 5-10 year performance-based contracts with clear renewal pathways to justify investment and build stability. The current short-termism is crippling.

-

Realistic Tariff Structures: Tariffs must allow operators to cover all costs (operation, maintenance, loan servicing, and a reasonable profit) sustainably. This requires transparent, depoliticised tariff-setting mechanisms.

-

Technical Backstopping: Establishing accessible technical support networks for maintenance and troubleshooting is crucial, especially for rural operators.

-

-

Blended Finance Done Right: Using donor funds for deep technical assistance, very concessional loan components, or guarantees tied to capacity building – not just de-risking standard commercial loans.

-

-

The Regime’s Cynical Calculus:

-

Offloading Responsibility: Promoting the “private sector solution” allows the state to offload the political and financial burden of direct service provision, especially in difficult rural areas. Failure can then be blamed on “inefficient operators,” not state neglect.

-

Maintaining Control: Short-term contracts and dependence on state-sanctioned loans (via BK) keep private operators on a tight leash, dependent on regime favour, preventing them from becoming truly independent forces.

-

The Mirage of Progress: Launching a loan product creates a tangible“achievement”” to showcase internationally (“See? We’re enabling the private sector!”), regardless of its actual impact or sustainability. It’s performance over substance.

-

Conclusion: Castles Built on Sand

Rwanda’s championing of private WASH operators, culminating in the Bank of Kigali’s high-interest loan, is exposed as a dangerous mirage. By wilfully ignoring Eng. Murekezi’s own diagnosis of “weak business planning” and “short-term contracts” – the foundational cracks in the sector – the regime and its partners are not empowering entrepreneurs; they are luring them onto quicksand with a loan for a bucket and spade.

-

Throwing debt at operators without fixing the crippling lack of skills and the perilous instability of their operating environment is not just negligent; it’s institutionalised sabotage. It commands them, against all odds, to build castles in the air, doomed to collapse under the weight of unrealistic expectations and unsustainable debt. The ruins will litter Rwanda’s villages – failed businesses, seized assets, and communities still waiting for reliable water and sanitation. True progress requires building foundations first: real capacity, long-term security, and viable operating models. Until then, the private sector “solution” remains a cruel illusion, setting up well-intentioned Rwandans for a fall engineered by Kigali’s indifference to the harsh realities on the ground. The sand shifts, the castle crumbles, and only the debt remains.

-

The Thirst Tango: Rwanda’s Choreographed Exploitation of Desperation

The aching need is visceral. In Rwanda’s thousand hills, the daily trek for water defines existence—women balancing yellow jerry cans on weary heads, children scouring dry riverbeds, clinics battling cholera outbreaks from contaminated springs. This genuine, desperate need for WASH investment is Rwanda’s open wound. Yet, at the Kigali Serena, the regime and its partners didn’t offer a balm; they staged a macabre dance on the blister, transforming human suffering into a propaganda spectacular. Launching a fundamentally flawed loan product as a “revolutionary solution” isn’t development; it’s a dark, heart-wrenching manipulation, a cynical exploitation of desperation for political theatre. As the British adage piercingly observes: “They weep crocodile tears over the thirsty, while standing guard at the well.”

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this exploitation:

-

The Raw Material of Suffering: The regime knows the power of the imagery. The statistics they suppress—the 12.3% with piped water, the 45% dissatisfaction—paint a picture of widespread struggle. The hours lost, the diseases borne, the girls kept from school: this is the emotional capital ruthlessly mined. They understand universal WASH access is an unassailable moral imperative, making any “solution” they offer appear heroic.

-

The Stagecraft at Serena: The launch was meticulously orchestrated propaganda:

-

Venue as Symbol: Choosing Kigali’s most opulent hotel screamed “progress” and “modernity” to foreign diplomats and donors, deliberately contrasting with the mud-brick struggles of Bugesera or Rubavu.

-

Stakeholder Theatre: Gathering 100 elites (ministers, bankers, NGO chiefs) created an image of “national unity” and “serious commitment.” The absence of actual water collectors or struggling operators was telling—this wasn’t for them, it was about them, without them.

-

Language as Weapon: Terms like “transformative,” “accelerating progress,” “unlocking potential,” and “innovative partnership” were deployed like artillery, drowning out critical thought in a barrage of benevolent-sounding jargon. The genuine need was reduced to a rhetorical prop.

-

-

The Problematic “Solution” as Hero Prop: The loan itself, with its predatory rates, exclusionary collateral, and donor dependency, was deliberately framed not as *a* tool, but as the solution. By presenting it amidst fanfare as revolutionary:

-

They Hijacked Hope: They tapped into the desperate longing for change, associating their flawed financial product with the dream of clean water. Offering debt became synonymous with offering dignity.

-

They Manufactured Achievement: The launch itself became the success story, generating headlines before a single loan was disbursed. The act of announcing was prioritised over the substance of the offer. Performance over progress.

-

They Deflected Scrutiny: By positioning the loan as the answer to the financing gap, they subtly shifted blame. The lack of water wasn’t due to state failure or corruption; it was due to the absence of this magical financial instrument. “Just wait for the loans to flow,” becomes the new mantra.

-

-

Partners as Unwitting (or Complicit) Props: UNICEF and Water For People’s presence wasn’t neutral. It bestowed instant legitimacy and moral authority. Their logos on the podium signalled to the world: “This is credible, this is good.” Their participation transformed a potentially controversial banking product into an unquestionable humanitarian endeavour. They became essential characters in the regime’s play, their credibility weaponised to validate the illusion.

-

Target Audiences:

-

International Donors & Investors: Projecting dynamism and “financial innovation” to attract more aid and investment. “See? Rwanda is tackling its problems smartly!”

-

Domestic Population: Offering a narrative of hope and state action, however illusory, to dampen discontent and reinforce the regime’s image as a proactive problem-solver. “Your government is working hard for your water!”

-

The Regime Itself: Bolstering its carefully cultivated image of technocratic efficiency and visionary leadership on the global stage (“Rwanda Rising”).

-

-

The Heart-Wrenching Cruelty: The profound cynicism lies in exploiting the most vulnerable. It uses:

-

A Mother’s Fear: Fear for her children drinking dirty water, transformed into gratitude for a debt trap.

-

A Community’s Exhaustion: Years of hauling water, twisted into hope for an unaffordable loan.

-

The Universal Desire for Dignity: The basic right to a safe toilet, perverted into a financial transaction with a bank.

-

Conclusion: Crocodile Tears at the Well

The Bank of Kigali’s WASH loan launch wasn’t merely ineffective; it was a profound act of psychological violence against Rwanda’s thirsty millions. By cynically exploiting their genuine, desperate need as a stage prop for a PR coup, the regime and its partners revealed a chilling disregard for human dignity. They transformed suffering into spectacle, offering not liberation from thirst, but the golden handcuffs of debt disguised as salvation.

-

“They weep crocodile tears over the thirsty, while standing guard at the well.” The Serena elites dabbed metaphorical tears for the water burden, even as their “solution” effectively guarded the financial and political structures that keep the well inaccessible to most. The champagne flowed, the speeches soared, and the loan was hailed—a grotesque tango performed on the cracked earth of Rwanda’s water-scarce heartlands. Until the crocodile tears dry up, and the well is truly opened through accountable governance, massive equitable public investment, and solutions built on reality, not rhetoric, the promise of water will remain just another cruel illusion, choreographed in Kigali’s gilded ballrooms while the hills remain parched. The thirst endures; the manipulation continues.

-

The Polished Key in the Rusted Lock: Rwanda’s Showcase Charade

Beneath the glossy brochures and Serena Hotel applause, Water For People Rwanda’s boast of reaching “1.5 million Rwandans” with “over $54 million invested” rings with a hollow, performative clang. It’s a textbook case of selective showcasing – parading isolated triumphs like gleaming trophies whilst the systemic failure to deliver piped, reliable, affordable water to the nation crumbles unnoticed in the background. This isn’t progress reporting; it’s a nostalgic séance summoning past endeavours to distract from present inadequacy. Like the British adage says: “The used key is always bright.” They polish the well-worn key of donor-funded projects, flashing its shine, while ignoring the rusted, broken lock of national infrastructure that remains stubbornly jammed.

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this deceptive showcasing:

-

The Seductive Shine of the “Used Key”:

-

The Big Numbers: “1.5 million reached! $54 million spent!” These figures are potent. They offer donors quantifiable “impact,” provide the regime with evidence of “partnership,” and give Water For People compelling fundraising fodder. They are designed to impress at face value.

-

The Implied Narrative: Showcasing these numbers suggests momentum, effectiveness, and a trajectory towards universal access. It implies, “See? We are making significant headway, thanks to these efforts.”* It’s a feel-good story of external intervention making a difference.

-

-

The Tarnished Reality: Systemic Failure Unmasked:

-

The Devastating Contrast: Eugene Dusingizumuremyi’s (WFP Rwanda) own admission at the same event provides the crucial counterpoint: Only 12.3% of Rwandans have piped water at home. This stark figure, consistently buried beneath the “1.5 million reached” headline, exposes the abject systemic failure.

-

What “Reached” Truly Means (and Doesn’t):

-

Ephemeral Interventions: Much “reach” comes from point solutions: a protected spring here, a borehole there, hygiene training in a village. These are valuable, but often temporary fixes vulnerable to breakdown, drought, or lack of local maintenance capacity. They don’t equate to permanent, integrated service delivery.

-

Ignoring Sustainability: Did the $54 million build systems that last and are affordably maintained? The low satisfaction rate (45%) and persistent reliance on distant sources suggest many interventions fail the sustainability test. Reaching someone once isn’t serving them reliably for decades.

-

The Piped Water Chasm: The $54 million and 1.5 million reached have made a negligible dent in the fundamental challenge: building the extensive, resilient network of pipes, treatment plants, pumping stations, and household connections required for true convenience and safety. This requires decades of coherent, well-governed, massively funded national infrastructure development – something demonstrably lacking.

-

-

The Affordability Void: Even where water exists, can people afford it? Showcasing “reach” says nothing about tariffs, connection fees, or the ongoing burden on household budgets. “Reached” doesn’t mean “served affordably.”

-

-

Nostalgia as a Distraction Tactic:

-

Focusing on the Past: Highlighting cumulative spend and beneficiaries since WFP arrived is inherently backward-looking. It dwells on inputs and outputs of past projects, not the current state of national service delivery. It’s like celebrating how many seeds you planted years ago while ignoring the fact the harvest failed.

-

Deflecting from Present Paralysis: This nostalgic showcasing subtly shifts focus away from the government’s contemporary failure to transform decades of aid and its own resources into a functioning, expanding piped water network. Why is progress on this fundamental metric so glacial? The showcase avoids this uncomfortable question. Look at the shiny key, not the broken lock.

-

-

Who Benefits from the Showcase?

-

Water For People: Validates their existence, justifies continued funding, and burnishes their reputation as an “effective” implementer. The complexity of systemic failure is inconvenient; simple metrics are bankable.

-

The Rwandan Regime: Provides “evidence” of progress and partnership, deflecting scrutiny from its own inability or unwillingness to drive the large-scale, complex infrastructure rollout and governance reforms needed for piped water. Allows them to say, “See? With partners like this, we are getting there!” while the 12.3% figure stagnates.

-

Donors: Offers tangible, reportable “results” for taxpayer money back home. Fits neatly into logframes and annual reports. The messy reality of systemic blockage is harder to quantify and explain.

-

-

The Cruelty of the Distraction:

-

For the woman in Ruhango still walking 3 km to a spring “protected” a decade ago – now often dry or contaminated – the “1.5 million reached” statistic is an insult. Her reality hasn’t fundamentally changed.

-

For the family in Gicumbi saving for a prohibitively expensive household connection while hearing of “$54 million invested,” it breeds cynicism and despair. Where did that money go, if not to pipes for us?

-

It perpetuates the cycle of aid dependency by suggesting scattered external interventions are the primary solution, obscuring the imperative for transformative national action.

-

Conclusion: The Bright Key, the Broken Lock, and the Thirst Unquenched

Water For People’s showcase of “1.5 million reached” and “$54 million invested” is a dangerous exercise in nostalgia and misdirection. It polishes the “used key” of discrete donor projects until it gleams, while the rusted, broken lock of Rwanda’s systemic failure to deliver piped water for all remains firmly in place. This selective spotlight on isolated inputs and outputs blinds observers to the devastating output that truly matters: only 12.3% of Rwandans have water flowing reliably into their homes.

-

True progress isn’t measured by cumulative spending or scattered beneficiaries of the past. It’s measured by the relentless, tangible expansion of piped, affordable, reliable water access today. Until the regime and its partners shift focus from showcasing the shine of the old key to shattering the systemic paralysis that prevents forging a new one – through accountable governance, massive equitable public investment, and long-term infrastructure planning – the majority of Rwandans will remain outside the showcase, gazing at its glitter while their throats stay parched. The key may be bright, but the lock is broken, and the house remains dry. The thirst, like the systemic failure, endures.

-

The Hollow Right: How Rwanda Sells Water by the Cup While Promising Rivers

When Gemma Maniraruta, Director General for Water and Sanitation at Rwanda’s Ministry of Infrastructure, solemnly declared that “access to WASH services is a basic human right” during the Bank of Kigali’s Serena launch, she articulated an unimpeachable truth. Yet, in the very next breath, the “solution” proffered – high-interest loans for operators and households – laid bare a staggering, thought-provoking contradiction. This is the “Human Right” Hypocrisy laid bare: proclaiming water an inalienable birthright whilst erecting a financial tollbooth staffed by bankers. It forces the agonising question: Can a fundamental human right truly be contingent on loan approval, creditworthiness, and the profit margins of a commercial bank? As the piercing British adage warns: “You cannot have your cake and eat it.” Rwanda’s regime wants the international acclaim for recognising the right, while forcing its citizens to buy the cake – slice by usurious slice.

Here’s a comprehensive dissection of this hypocrisy:

-

The Unassailable Principle: Maniraruta is absolutely correct. International law (UN Resolution 64/292), Rwanda’s own constitution (Article 23), and basic morality affirm that safe water and sanitation are fundamental human rights, essential for life, health, dignity, and equality. This imposes a duty on the state to ensure availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality for all, without discrimination. It’s non-negotiable.

-

The Pernicious Commodification: The Bank of Kigali loan scheme fundamentally commodifies this right:

-

Access Through Debt: For households needing connections or sanitation facilities, and for operators needing capital, access becomes mediated by debt. The right is transformed into a financial transaction with a commercial entity seeking profit.

-

Profit Motive Over Public Good: BK’s core obligation is to shareholders, not human rights. Charging 10-14% interest prioritises bank profitability over the affordability and universality of the service. The right is subordinated to the balance sheet.

-

Gatekeeping by Creditworthiness: Loan approval hinges on collateral, business plans, and credit history – concepts utterly alien to the inherent nature of a human right. Does a mother in Gicumbi lose her child’s right to safe water because she lacks land title? Does a community water association in Nyamagabe forfeit their right because their financial projections are deemed risky? The scheme answers: Yes.

-

-

The State’s Abdication & Perverted Logic:

-

Shifting the Burden: By championing this loan as a primary solution, the state effectively abdicates its core duty. Instead of mobilising public resources, guaranteeing investment, or regulating for universal service, it outsources the fulfilment of a human right to the market and the debt capacity of its poorest citizens. It’s a dereliction of constitutional duty disguised as “innovation.”

-

The Contorted Justification: The regime’s logic seems to be: “We recognise the right, but fulfilling it costs money. Therefore, you (the user or small operator) must borrow it commercially, with interest.” This perverts the principle. The cost of fulfilling a human right is a state obligation, to be met through taxation, efficient resource allocation, and prioritisation – not user debt. Imagine applying this logic to the right to a fair trial: “Justice is your right, but the court costs £10,000 – here’s a loan at 14%.”

-

-

The Rwandan Reality: Rights vs. Rents:

-

The Urban Poor: A family in a Kigali informal settlement hears “water is your right,” but connecting their shack requires fees and potentially a loan they cannot afford. Their “right” remains out of reach, monetised.

-

The Rural Woman: A woman in Kayonza spends hours hauling water. Her “right” to accessible water isn’t fulfilled by public investment in pipes; it’s supposedly addressed by offering a loan to a distant operator, who may charge tariffs inflated by 12% interest. Her burden is merely financialised, not lifted.

-

The Struggling Operator: A small sanitation provider is told they are delivering a “human right,” yet they must take on predatory debt to buy a truck, risking ruin if repayments falter. They become debt-serfs to the right they are meant to uphold.

-

-

The Hypocrisy Amplified by Partnership:

-

UNICEF & Water For People’s Complicity: These organisations, mandated to uphold children’s rights and human dignity, lend their credibility to a scheme that makes access to a fundamental right contingent on commercial debt. Their participation sanitises the commodification, blurring the lines between humanitarian principle and financial extraction. Do rights-based organisations endorse payday loans for water?

-

Conclusion: The Cake Gorged, The People Starved

Gemma Maniraruta’s invocation of WASH as a “basic human right” rings tragically hollow against the clinking of the Bank of Kigali’s cash register. The regime’s approach is the epitome of “having your cake and eating it”: gorging on the international prestige of recognising the right, while forcing the Rwandan people to pay – often through crippling debt – for the crumbs.

True commitment to water as a human right demands massive, equitable public investment, robust regulation ensuring affordability and non-discrimination, accountable public utilities, and prioritisation in national budgets. It does not demand indebting mothers for their children’s hydration or gambling community health on an SME’s ability to service a 14% loan.

-

This loan scheme isn’t a pathway to realising the right; it’s a perversion of it. It transforms a universal entitlement into a privilege contingent on credit scores and bank profits. Until the Rwandan government abandons this financial sophistry and embraces its non-negotiable duty to mobilise public resources and govern effectively to deliver actual universal access, its pronouncements on human rights will remain just that: pronouncements. Empty words echoing in Serena ballrooms, while the hillsides thirst. The cake is consumed by the state and its banking partners; the people are left scraping the plate. The right remains inscribed on paper, denied in practice.

-

The “Emerging” Mirage: How Rwanda Rebrands Decades of Water Failure as a Startup Opportunity

When Darius Mukunzi, Bank of Kigali’s Head of SME Banking, leaned into the microphone at the Serena and described Rwanda’s water, sanitation, and hygiene sector as“emerging”” – justifying special loan terms and reduced collateral – it wasn’t merely an observation. It was a calculated narrative sleight-of-hand, a corrupt recalibration of history worthy of Orwell. Framing WASH as some plucky startup sector ignores the brutal truth: providing clean water and safe sanitation has been a fundamental, unmet human need in Rwanda for generations. Labelling it “emerging” implies recent, vigorous effort, absolving decades of state failure – colonial, post-independence, and post-genocide – while laundering present neglect as “pioneering potential.” It’s like calling a dilapidated, colonial-era pipe “cutting-edge infrastructure” because you slapped a fresh coat of paint on a leaking joint. As the British adage acidly observes: “Old sins cast long shadows” – and Rwanda’s water crisis is a shadow stretching back far longer than this convenient “emerging” fiction admits.